You’re at the entrance of a bar. The bouncer asks: “Are you over 18?” What if you could prove you are without revealing your exact age, your birth date, your address or anything else on your ID? At first glance, that sounds impossible and you wouldn’t be the first to think so. In fact, the early reviewers of the groundbreaking academic paper in zero-knowledge cryptography, “The Knowledge Complexity of Interactive Proof Systems”, were similarly skeptical. The paper was rejected multiple times before it was finally published in December 1985, exactly 40 years ago. Two of its authors, Shafi Goldwasser and Silvio Micali, were later awarded the Turing Award in 2013, often described as the Nobel Prize of computer science, for their foundational contributions to zero-knowledge proofs and modern cryptography.

If you had asked whether zero-knowledge proofs(ZKP) had real-world applications nine or ten years ago, the answer would likely have been vague or speculative. Today, however, the story is very different. In the blockchain, transaction history is transparent and every validator of the network re-executes every transaction. The systems critically lack two components: privacy and scalability. While desperately looking for ways to fix those gaps, the blockchain space found exactly what it needed in ZKP. That’s why zero-knowledge proofs are often portrayed as a kind of panacea. It’s common to see crypto Twitter describing ZKP as the ultimate solution. Even Ethereum’s evolving roadmap has discussions about moving beyond the Ethereum Virtual Machine(EVM) toward a RISC-V–based execution environment fully based on ZK, signalling that something significant is coming. And projects like Midnight Network and Mina are built from the ground up using the principles of zero-knowledge protocols.

One of the first notable real-world applications of zero-knowledge proofs was the launch of Zcash in 2016, where shielded(private) transactions on a public blockchain became a reality. Zcash started as a paper written by cypherpunks and researchers. The launch of Zcash was a very impressive feat of research and engineering applied to an end product and system. In addition to privacy, ZKP generates succinct proof that guarantees correct execution of operations. This way, the participant can verify this succinct proof rather than re-execution. And since around 2019, zero-knowledge technology, alongside optimistic approaches, has helped Ethereum scale significantly. This showed people that it was possible and practical to use ZKPs in the real world. This has also led to an explosion of research and engineering efforts in the field, especially in recent years. But what is a zero-knowledge proof, really? And how does it apply in the real world?

Let's dive in.

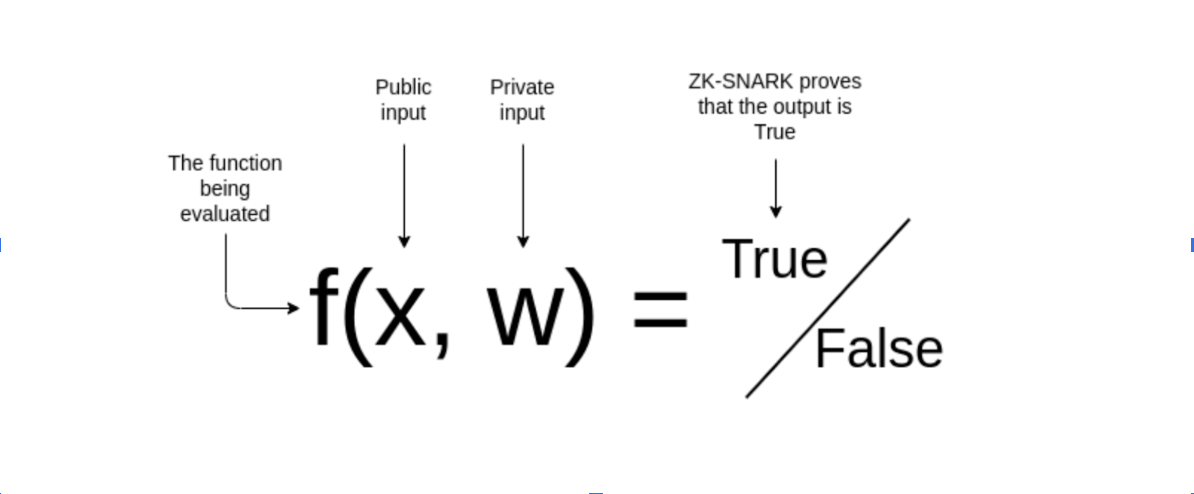

Spoiler: ZK is kind of like an oracle that reveals nothing except a yes/no answer.

Zero-knowledge proofs enable you to prove a statement without revealing any information other than what you are willing to selectively disclose. In doing so, the verifier learns nothing more than whether the claim is correct. We have two parties in the protocol: the prover and the verifier. The prover generates a proof and tries to convince the verifier, while the verifier checks the proof’s correctness. The most common example to demonstrate zero-knowledge proof is age. As a 25-year-old man using zero-knowledge proofs, I can convince you I’m over 18 without telling you my exact age or even my year of birth and if I were lying, you would know. Sounds interesting, right? For many of us, this is a hard concept to wrap our heads around. In fact, a wide variety of examples are used to build intuition for zero-knowledge proofs, such as Where’s Waldo, Ali Baba’s cave, Hamiltonian path, 3-colorability, or even a deck of cards. The following example is my favorite because it provides particularly clear intuition.

Let’s say you have a friend who has trouble with his taste buds and cannot differentiate between Pepsi and Coca-Cola and thinks both taste the same. Since both drinks have the same color, he can’t visually tell which is which without tasting. You, however, want to prove to your friend that they are in fact different drinks without revealing which one is Pepsi and which one is Coca-Cola. To do this, you bring two bottles with no labels on them. You ask your friend to pour a cup from one bottle into one glass, and a cup from the other bottle into a second glass. You taste both drinks once so that you know which glass contains which drink. Then, you close your eyes and ask your friend to either swap the glasses or leave them as they are. Afterward, you taste the drinks again and tell him whether the order was changed. In cryptographic terms, the intuition relies on an honest verifier; handling a malicious verifier requires stronger constructions (e.g., protocols proven secure against malicious verifiers or compiled via standard transformations).

If you were guessing randomly, you’d have a 50% chance of being correct in the first round. If your friend repeats this experiment multiple times, the probability that you’re merely guessing correctly every time becomes extremely small. After 10 rounds, the probability of succeeding by pure guessing is (1/2)¹⁰ or 1 in 1024. Because you can genuinely distinguish the drinks by taste, you’ll answer correctly every time. After a while, your friend becomes convinced that the two drinks really do taste different—and may even consider consulting a medical specialist—without ever learning which glass contained Pepsi and which contained Coca-Cola. The only information he gains is that the claim “the drinks taste different” is true.

One important thing to notice in this example is that zero-knowledge proofs are not like traditional mathematical proofs with a 100% guarantee. Rather, as described in the original paper, they are probabilistic in nature, often called an argument of knowledge. A verifier may be erroneously convinced of a false statement only with negligible probability, and correctly convinced of a true statement with very high probability (often written as 1−negl(n) where the value negl(n) decreases exponentially (1/2)ⁿ.

Another important aspect is that there is an ongoing interaction between the prover and the verifier, which makes the proof interactive. Indeed, the first zero-knowledge proofs were interactive proofs.

Later on, non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs were introduced. For a zero-knowledge system to qualify as a proof, whether interactive or non-interactive, it must satisfy the following three properties.

Completeness: If the statement is true (e.g., “if indeed I am 25 years old”), an honest prover can convince an honest verifier.

Soundness: If the statement is false, no cheating prover can convince the verifier, except with negligible probability. For example, proof verification fails if I claim I am more than 30 years old.

At first glance, completeness and soundness may seem redundant, but they’re not. A proof system can be complete without being sound: for example, if it accepts every statement (including false ones), it is complete but not sound. Conversely, a proof system can be sound without being complete: if it never accepts any statement, it never proves a falsehood, but it also never proves a true statement.

Zero-knowledge: The verifier learns nothing beyond what the prover wants to reveal of the statement (they can be sure I’m over 18, but never my exact age).

This last property is what makes zero-knowledge proofs more interesting compared to other cryptographic techniques like fully homomorphic encryption or secure multi-party computation. Those techniques aim to protect data during computation, but they still involve encrypted information that could be recorded today and attacked later (“store now, decrypt later”) if the underlying cryptography becomes weaker in a post-quantum world. In contrast, a zero-knowledge proof is designed to reveal no hidden payload beyond “yes/no,” so even if you have a quantum computer, there’s nothing like a secret message inside the proof to decrypt later. In addition, modern zero-knowledge proof systems are largely information-theoretically secure, except for certain cryptographic components which will be discussed later. The primary post-quantum risk for zero-knowledge systems lies in the soundness property rather than zero knowledgeness. In some cases, quantum computers could break the cryptographic assumptions behind elliptic curves that give the system its guaranteed soundness and create a false proof. This isn't a unique problem only for zero-knowledge proofs but neither are the signature schemes securing most chains (e.g., Bitcoin’s ECDSA), so post-quantum migration is a broader cryptographic transition, not a zkSNARK-specific problem.

Zero-knowledge proofs started out as interactive proofs, but that interaction isn’t well-suited to many real-world systems because the prover and verifier have to be online at the same time to exchange information. Thankfully, the Fiat–Shamir transformation later made it possible to turn many interactive proofs into non-interactive ones. It took me a while to understand how Fiat–Shamir works, so I’ll try to describe it in simple words. In the interactive version, the verifier keeps sending you random challenges. With Fiat–Shamir, instead of the verifier giving you those challenges, you generate them yourself by running a random oracle model for example, hash function, on everything that’s been said so far (you commit to a value before the challenge).

The challenge is not truly random in the literal sense, it’s deterministic, but we treat a good hash function as behaving like random for this purpose. A good metaphor is a job interview. Let’s say you believe you qualify for a job. In a live interview, you explain your expertise and the interviewer asks you a follow-up question on the spot. Now imagine you can’t do a live interview, so you submit a recording—but the follow-up question is generated from the recording itself in a way you can’t predict before you finish recording. If you try to cheat by recording a different video, the generated follow-up question changes too. In the real world, that “question generator” is the hash function. I hope this gives you the intuition.

We’ve been exploring ways to make ZKP easily usable, but there’s still a big practical problem. If you generate lots of challenges (like in the Pepsi/Coke example), doesn’t the proof get bigger? Yes, you’re exactly right. If you “challenge” the statement many times, the transcript grows, and this kind of proof can become pretty large. For example, in early Zcash-style private transactions, the proof-related data included in a single transaction could be on the order of ~1–2 KB. A major breakthrough came in 2016, when Jens Groth introduced Groth16. What made Groth16 feel revolutionary in practice is that it gave you a small-size proof (basically just a few elliptic-curve group elements) and very fast verification, even when the computation you’re proving is huge.

These proofs fall under SNARKs, which stands for succinct non-interactive argument of knowledge. “Succinct” is just another word for small: Groth16 lets you create a proof that’s only a few hundred bytes in practice. Of course, it has tradeoffs. The big one is the trusted setup. I won’t go in detail to the trusted set up. Basically it is a common public parameter both verifier and prover agreed upon before the proof generation starts. Groth16 needs a one-time setup phase that produces the public parameters everyone will use later to create and verify proofs. Also, Groth16’s setup is typically circuit-specific—and by “circuit” in ZK terms means the exact set of constraints that represents the computation you’re proving. so you have to redo the setup for each new circuit. Later, PLONK-style systems were introduced, and one big reason they became popular is that they support a universal (and often updatable) ceremony: instead of doing a trusted setup for each circuit, you can often reuse one setup across many circuits (up to some size bound). You can take a further look about trusted setup here. Midnight Network uses a PLONK-family proving system via Halo 2.

Another type of non-interactive proofs are STARKs, which stands for Scalable Transparent Argument of Knowledge. They’re often described as “transparent” because they don’t need a trusted setup, and they rely heavily on hash-based primitives (Merkle/hash commitments) rather than pairings. A common selling point is that their security assumptions are considered post-quantum-friendly (at least compared to elliptic-curve/pairing-based SNARKs), but the tradeoff is that STARK proofs are usually much larger than SNARK proofs. In practice, you’re often choosing between a SNARK proof on the order of hundreds of bytes and a STARK proof on the order of hundreds of kilobytes and that single factor can be a deal-breaker depending on what you’re building. There are also other types of ZK proofs like Bulletproofs, which are not as widely used today. Bulletproofs don’t require a trusted setup and they’re especially strong for range proofs, but they aren’t succinct in the SNARK sense: proof size and verification scale roughly with the size of what you’re proving, so they get less attractive as statements grow. Monero, uses bulletproofs to build its privacy preserving chain.

One unresolved question is: how secure are zero-knowledge proofs, really? For example, many commonly used zk-SNARK systems rely on polynomial commitments built on elliptic-curve cryptography which are vulnerable to quantum attacks because quantum computers threaten the underlying curve assumptions. This is the main component that needs to be replaced in a post-quantum setting. As a result, different approaches are being explored. Ethereum is investigating FRI commitments, which use hash-based commitments (STARKs) instead of polynomial commitments. Meanwhile, projects like Midnight are exploring post-quantum ZK directions based on lattices(Snarks). Hash-based approaches are already widely used and well understood, but they often come with bigger proofs. Lattice-based approaches aim to offer post-quantum security the additional advantage of keeping proofs relatively small due to the mathematical properties of lattices.

Okay, now you’ve got a good grasp of ZKPs but one question still remains. We’ve laid out how to prove the “two different tastes” claim, and if you’re a good programmer, with a bit of trial and error you could convert that protocol into code. But it raises another issue: do we really have to redesign every proof as a custom protocol from scratch? And doesn’t that often require real cryptographic knowledge? That’s where zero-knowledge domain-specific languages (zkDSLs) come into play. In many ZK systems, you still have to represent your computation as a circuit (constraints/equations the prover must satisfy). A zkDSL is a special kind of language that helps you write those constraints in a way that feels closer to normal programming with syntaxes close to Typescript and Rust, without manually “designing a circuit” by hand every time. Some of the earliest widely-used examples are Circom, and libraries like arkworks. More recent zkDSLs include Noir, Midnight’s Compact language and Mina’s o1js. Using these domain-specific languages, you can take a computation you care about and express it in a “provable” form, so you can generate proofs without needing to become a cryptographer first.

Last but not least, let’s look at the applications of ZKP. Electronic cash is a good starting point. In Bitcoin’s original design (2009), every transaction is public. That wasn’t necessarily an “engineering feat”, it’s largely because the easiest way to make transactions verifiable without a central party is to make the ledger transparent. But with ZK, we can make transactions verifiable and private at the same time. More broadly, while blockchains brought censorship resistance and openness to anyone in the world, their transparent nature has also been one of the biggest barriers to adoption. With ZK, it becomes possible to build things like: Anonymous voting, prove you’re eligible to vote without revealing who you are. Anonymous signaling / whistleblowing: prove you belong to an organization without revealing your identity—making the whistleblower both safer and more credible. ZK rollups: execute a high volume of transactions off-chain, then post a succinct proof on-chain to prove the result is correct.

ZK-EVM: a system that proves Ethereum-style smart contract execution in zero-knowledge, so you can verify EVM computation with a proof. ZK-VM: a general-purpose virtual machine where any computation can come with a proof—so you can verify the output without re-running the computation yourself. I am especially excited for ZKVMs.

In my next blog, I’ll discuss the other major application of zero-knowledge proofs: succinctness and verifiable computation. And in the upcoming posts, I’ll get into the nitty-gritty details of ZK proofs, including a code walkthrough to see how zero-knowledge works in action.